Church of England Article By Lord Taylor of Warwick

Sky News gave me a daunting task last week – to analyse the disasters caused by the earthquake in China and cyclone in Myanmar (formerly Burma) – in five minutes. Daunting since it has already taken me over 30 years to equate natural disasters with a God of love. Since God is all-loving and all-powerful, why does He let such disasters happen?

gave me a daunting task last week – to analyse the disasters caused by the earthquake in China and cyclone in Myanmar (formerly Burma) – in five minutes. Daunting since it has already taken me over 30 years to equate natural disasters with a God of love. Since God is all-loving and all-powerful, why does He let such disasters happen?

The Bible does have examples of natural disasters used by God as a means of judgement and punishment, such as the plagues in Egypt. God also protected his people during times of famine or drought. The Bible shows God in charge of natural forces. So what can we learn from the dreadful catastrophes, currently happening in Western China and Myanmar`s Irrawaddy delta?

An earthquake and cyclone are examples of an imperfect world. But that is not how God originally created and intended it. Man’s sin, through self-will and disobedience, also affected the natural world. The original balance and harmony were upset. Natural disasters are a dramatic reminder that we live in an imperfect fallen world. But God does not look on dispassionately when such traumatic events cause death, disease and homelessness.

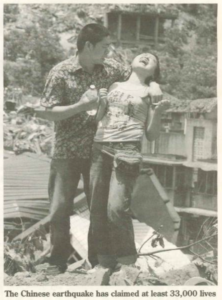

When I look at the television images and the press photographs of dead or injured children, taken from the rubble of these recent events, my heart immediately goes to my own children. It is the only way I can identify with the heartache that thousands of people, affected by the earthquake and cyclone Nargis, must be feeling. The tragedy of a lost child in China is magnified by their Governments one child per family law. But God suffers when we suffer. God does know what pain, hardship and separation are like. Because of his love for us, God was prepared to come to Earth in the person of Jesus and suffer the agonizing death of crucifixion. So God does share the tragedy of disaster victims.

In the Bible, suffering is recognized as a fact of life, but we are taught how to cope with it Peter wrote: “Christ himself suffered for you and left you an example, so that you would follow in his steps. When he suffered, he did not threaten, but placed his hopes in God, the righteous Judge,” 1 Peter 2:21-23.

Natural disasters also act as a sober reminder of the uncertainty and brevity of life. Death can strike anybody, anywhere, at any time. They make us confront spiritual and eternal realities. It is ironic that another part of the world which is susceptible to earth tremors and other natural hazards – albeit on a lesser scale – is Southern California.

I have had the privilege of working in Western China and Beverley Hills. Two years ago I was speaking at a conference in Sichuan Province. It is thought that as many as 50,000 people may have died there, following Nargis. Then only recently, I returned from glamorous Hollywood, where I was presenting some film awards, as Vice President of the British Board of Film Classification. But despite the outward material differences between these two parts of the world, the locals in Southern California also live with the fear of sudden land shifts and bush fires.

Yet even out of evil, good may come. Paul wrote to the Romans: 8:28: “We know that in all things, God works for good with those who love him, those whom he has called according to His purpose”. So disasters and the suffering they cause can prompt compassion, financial and practical giving by others who feel moved to help. This comes from Governments, charities like the Red Cross and countless individuals around the world – demonstrating God’s love and compassion.

But God’s offer of love is not forced on us. It is an offer we can refuse. The Chinese Government, unlike the previous regime under Chairman Mao, is learning to be more open with the rest of the world. When an even deadlier earthquake struck Tangshan in 1976, at least 250,000 died – but the truth was not revealed for months – and offers of foreign help were spurned. Since then, modern technology– the mass availability of mobile phone and internet pictures – and the upcoming Olympic Games in Beijing are factors making the Government more open to help from other nations.

This is in vivid contrast to the Myanmar military Junta, who stubbornly refused all but a trickle of aid to help the victims of cyclone Nargis, which may have killed over 130,000 people. The generals are so frightened they may lose power through foreign ‘interference’, they are willing to see their own people perish. An answer to the impasse may lie in aid being distributed through Myanmar’s neighbours, in the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) – including Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia.

This is in vivid contrast to the Myanmar military Junta, who stubbornly refused all but a trickle of aid to help the victims of cyclone Nargis, which may have killed over 130,000 people. The generals are so frightened they may lose power through foreign ‘interference’, they are willing to see their own people perish. An answer to the impasse may lie in aid being distributed through Myanmar’s neighbours, in the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) – including Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia.

As this article goes to press, the Junta now appears to welcome the ASEAN aid plan. The Junta tried to block aid- but they could not block prayer.